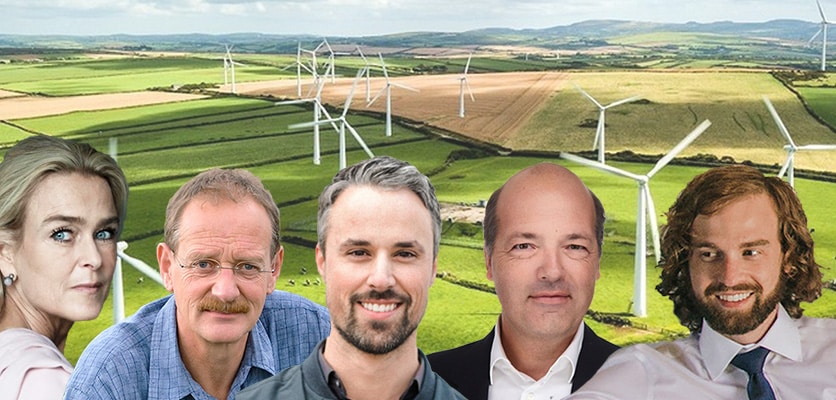

Tune into the ‘Targeting Zero Carbon in Food & Ag’ session, featuring Barbara Baarsma, CEO of Rabo Carbon Bank; Paul Gambill, CEO of carbon marketplace Nori; Béla Jankovich de Jeszenice, chairman of Commonland; Matt Marshall, senior director of corporate strategy for Nutrien; and Ken Giller, professor of plant production systems at Wageningen University & Research.

Paul Gambill spent his early career as a software engineer making mobile apps for Fortune 500 companies. In 2015, he reached an inflection point that eventually led to the creation of Nori, a blockchain-based carbon removal marketplace.

“Climate change was kind of staring me in the face,” he says. The problem preoccupied him far more than corporate app design. “I was thinking, perhaps naively, ‘well, the problem is too much greenhouse gas in the air, so then the solution is to pull those gases back out and store them somewhere’.”

In other words, climate change was an engineering problem, Gambill thought.

Gambill organized a networking forum in Seattle, where he lived, and quickly his thinking around the problem of climate change evolved. “I started realizing, this is not fundamentally a technology problem. We’re not missing technology,” he explains. “The problem is we know what to do; we’re just not doing it. To me, that speaks to a lack of incentives.”

Gambill and Nori are among the many diverse stakeholders tackling the issue of climate change by trying to improve and accelerate the global carbon markets—specifically, carbon capture in farmland soil. The market is nascent but growing, and with it, a lot of complex questions around just how much carbon can be removed and stored in the world’s soil systems and for how long; what are the best practices for soil carbon sequestration; how do those get measured and verified; what policy is needed, if any, to ensure that farmers see value.

There’s no choice but to figure them out, says Gambill. “Globally, we emit about 50 billion tonnes of CO2-equivalent every year. That seems likely to stay at that number, or even grow in the coming years.”

To meet the 2015 Paris Agreement global climate goals and avoid more devastating impacts of a warming planet, carbon removal from the atmosphere is increasingly viewed as a necessary measure, alongside dramatic greenhouse gas emissions reduction.

“Ideally, we should get to a point where we’re removing, globally, somewhere between 50 to 75 billion tonnes of CO2 per year,” adds Gambill.

Soil sequestration’s promise

Agriculture offers a significant opportunity in this regard. Soil naturally stores and retains CO2; what’s more, soil CO2 content is critical to landscape health and biodiversity.

Researchers like Ken Giller, professor of plant production systems at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands, caution about over-estimating the role that farmland can play in correcting the global carbon footprint.

“My concern on carbon capture in agriculture is that the potential amounts that can be sequestered are being vastly overestimated. Particularly in grassland systems, carbon capture is often temporary,” he says. “Emphasis on reducing greenhouse gas emissions such as methane and nitrous oxide is probably more important.”

Nevertheless, soil carbon sequestration has an important complementary role to play: soil carbon’s maximum potential could account for five to 10 billion tonnes of carbon removed per year, Gambill guesses. “So it’s significant, but it’s not the whole solution.”

The problem is that modern agricultural practices, from mono-cropping to excessive synthetic chemical use, contribute to climate change, rather than mitigate it. What’s needed is a radical shift to regenerative farming practices that replenish the natural ecosystem.

But there’s a cost to doing that, and much of it currently lands on farmers.

“Let’s face it, it’s a well-known story that in the agricultural value chain, farmers’ margins are minimal,” says Bela Jankovich de Jeszenice, himself a regenerative farmer and chair of the board of Commonland, an organization supporting land restoration initiatives.

Using cover crops, for example, which replenish the soil between harvests but rarely have market value, can cost farmers $60 per hectare. By comparison, lucky farmers can expect to fetch $15 to $20 per tonne, based on today’s carbon market trading rates.

Also, Jankovich adds, “measurement of carbon in the soil is a challenge because the cost of taking soil samples is high.”

New agricultural technologies offer some promise in curbing costs. Remote sensing startups, for example, could potentially bring down the cost of soil sampling. And, says Jankovich, “There are ways to do it with models, and many are working on those.” Separately, US-based CoverCress has developed a cover crop variety that can be harvested and sold to make seed oils, giving farmers an additional income stream. (Cover cropping is a key strategy used by farmers to improve soil health and thus the ability to store carbon.)

Demand for carbon credits is accelerating worldwide, as large companies look to offset their greenhouse gas emissions by paying for sequestration and removal. More than 1,500 corporations have pledged to zero-out their carbon footprints by 2050 at the latest. This will ultimately push the price of carbon up.

But for long-term financial sustainability, farmers would need to earn €50 to €75 per tonne ($60 to $90) of carbon, estimates Jankovich. “Early adopters will join carbon sequestration programs with lower carbon prices. But in order to realize a large shift in uptake of regenerative farming practices based on carbon market participation, this is the level of carbon pricing we should think of.”

There are signals that those prices are coming. The new administration in the US pegged the “social cost of carbon” at $51 per ton to account for a wider range of climate impacts. The Canadian government last year unveiled a plan that would raise the tax on carbon emissions per ton to C$170 ($135) by 2030.

Incentivizing carbon markets

For now, however, what is needed are incentive programs that enable farmers to shift to regenerative practices.

Europe has subsidies in place that support farming practices already. “There will be a new seven-year subsidy cycle starting in 2023, with an increased focus on these eco-system services as part of Europe’s Green Deal,” explains Jankovich. “Expectations are that it will consider how to go about carbon credits.”

He adds: “I hope that whatever comes out of this will increase the position of the farmer in the value chain because that position is not very strong right now.”

In the US and Canada, carbon market actors say there is also a role for government legislation, such as supporting administration and measurement requirements, offering farmers retroactive payments, or creating “stackable incentives” through a blend of subsidies and cost-sharing measures that lower farmers’ costs to entering the carbon markets.

“There are opportunities for government legislation to complement the development of the marketplace,” says Matt Marshall, senior director of corporate strategy for Canadian fertilizer company Nutrien. He cautions against legislation that is too onerous or directive in the early days of the carbon markets’ development, however. “There needs to be an environment where, from a grower perspective, there’s significant flexibility to pursue different pathways to value. Any legislation [should] provide multiple avenues to incentivize growers.”

For example, Nutrien’s carbon strategy, which aims to help the more than 500,000 growers in its network verify farm-level carbon performance farm level and sell credits, is highly experimental.

“We’re standing up a portfolio of pilots, in partnership with a broad base of suppliers, downstream consumer packaged goods companies, NGOs and execution partners to incentivize a comprehensive set of sustainability practices. These include practices that reduce GHG emissions and improve soil carbon sequestration, which will generate carbon credits utilizing several recognized protocols and standards,” explains Marshall. “This will help us establish the most viable and scalable path to create verified carbon credits going forward.”

The company is also working at individual points in the carbon value chain. Through US-based agricultural and soil science company Waypoint Analytical, which Nutrien acquired in 2018, the company hopes to contribute to “refining and evolving the methodologies around carbon measurement” in soil, adds Marshall.

For Nori, its solution is also in the early, experimental stages. The company has designed its own carbon trading “token” that can purchase one tonne of carbon on the platform. Nori’s hope is that by restricting the number of tokens trading, the value of the token will increase, “which then increases the incentive for suppliers to enter the market,” explains Gambill.

The token got its test run last October when Nori sold its first 5,000 carbon credits, priced at $15 per tonne.

Material impact

Like Marshall, Gambill worries about policy and regulatory interference in the carbon markets too early. “There are so many companies out there that are trying to develop new technology for improving and decreasing the cost of measurement and verification of soil organic carbon,” he says. “I don’t think the government should be in the business of picking winners and losers.”

That means private players in the carbon markets have to be able to effectively self-regulate while ensuring the impact on the environment is material. And for that to happen, there needs to be greater alignment around protocols and processes for measuring and tracking soil carbon storage over time.

“It’s hard to measure and monitor for carbon credits. This can only really be done by monitoring adopted practices,” observes Giller. “I think this is an important sticking point that will often come back in the discussion.”

Underscoring Giller’s point, the team at Nori is seeing widely varying estimates for how much carbon farmers’ should expect to be compensated. Nori conservatively estimates that farmers can sequester about a half tonne per acre. “I’m seeing other companies make claims that if you’re a farmer, you could earn one to four tonnes per acre per year. Some quotes are as high as eight to 12 tonnes per acre.”

Such examples are cause for concern, Jankovich says. “You don’t want there to be mistrust in the system in five to 10 years’ time because we can’t convincingly verify evidence of carbon sequestration on a plot of land.”

The antidote has to be a steadfast commitment to measurement rigor and detail, he adds. “Agriculture is about natural systems, so this is about capturing these natural systems in processes and models and getting the nitty-gritty details right.”

Source: Agfunder

—